|

|

|

|

|

|

|

POINTS OF CONDENSATION IN A CONTINUOUS STREAM OF THOUGHT |

|

|

The works of Gerrit van Bakel (1943-1984)

...but in the end it is the power of the imagination that gives rise to the world

DE PEEL

De Peel, the region that covers a part both of East Brabant and Central

Limburg, was not only Gerrit van Bakel's principal source of inspiration,

it was quite literally the ground of his being. This was where he had his

roots.

He was born in 1943 in the village of Ysselsteyn and he died there in

1984 in Deurne, the place where he had lived for a number of years and

where he produced his most important works. He felt such strong emotional

ties with this countryside and the hard existence of the generations

of farmers who had lived here, that he never wanted to leave it. 'I have an

identity here that is confirmed by every blade of grass and I don't have

this if I am in the Camargue, for instance, because I don't know the

blades of grass there. (1)

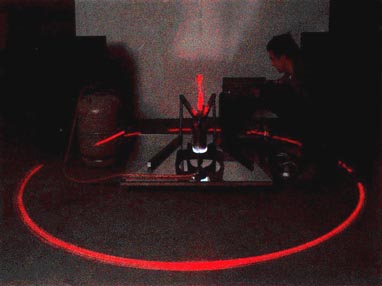

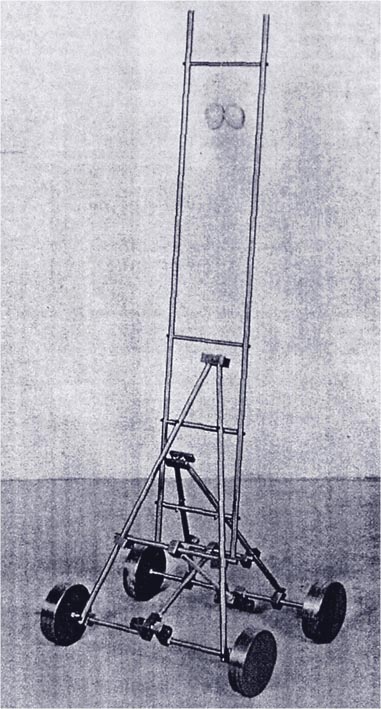

Right: Back to the source of the search for the origin of

Albinoni's grief (1980) |

|

|

|

As the son of a farmer he loved the land, with its

seasons, its cycle of sowing, the cultivation of the crops and the harvests,

but he also witnessed the great changes that took place in farming in de

Peel after the Second World War. He saw how through the arrival of

agricultural machinery and ever-increasing management efficiency the

harmonious relation between the farmer and his land slowly disappeared:

the harmony of the cart track, as he called it. 'I am interested in recapturing

a certain harmony. I am forty years old and I know what it is to have

walked in a cart track. In the meantime this cart track has disappeared. I

intend to find out what has happened to it. When I was a little boy, Deurne

where I lived was the most backward agricultural region of Europe. Now

it is one of the most modern regions. What has happened? I have felt the

pain involved in the disruption of this harmony. I really don't care whether

a rope of hemp is better than one made of nylon. I want to know in what

way I can preserve my own harmony and in what way I can hand

information down to the future. This is why I go in search of it, and this is

why I give it form. It is something I can't do directly. My arguments aren't

words but objects. (2)

There are also some works in which his native soil plays a central and

concrete role, such as the Papin machine, 1981, the 'Eindhoven presence machine',

1980 and the 'World trolleys', 1982-1984.

The choice of a site for a project that he had worked on for years and

which was never completed, 'Glowing Man', is also proof of the significance

he attached to the soil where he was born. He took it for granted

that this project would only be realized towards the end of his life. The

site he had planned for it was in between the village he was born in,

Ysselsteyn, Helenaveen, where he took up residence in 1966 after his

years as a student and the village of Deurne where he lived and worked in

his later years. Van Bakel considered that this piece of ground would be

the point where many lines in his work, his ideas and his personal life

would converge. 'In the project, 'Glowing Man' all ideas about place, time

and identity, inherited tradition and communication will be brought to-

gether. (3) Dees Linders, who has studied Van Bakel's work in depth, gives

the following description of the many different meanings of the 'Glowing

Man' as follows: 'In January and February, 1981, the first major exhibition

of his work was held in the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

In this exhibition his plans could be seen for the 'Glowing Man', a project

that was not only not completed but had hardly been begun and which

remained however an extremely important one for Van Bakel. A map was

drawn with a dot, the Glowing Man Point, which is the central point of a

network of connecting routes. This point is in fact a piece of undeveloped

ground in de Peel, a no man's land: a strange and silent spot from which

in theory every part of the world is accessible by old roads and new, along

cart tracks, by bicycle, by car, by boat, train or plane. For Van Bakel this

was also the invisible borderland between important areas and events

from his own life story. In this project he makes a connection between his

own personal life story and the whole world and the universe. His plan was

to buy pieces of land around this crucial point, including the elements

that already stood there and to create the existence there that he wanted.

Along the railway track that goes from the Hook of Holland to Vladivostock

and Abadan, notice boards would be placed. He planned an inundation

system for the water of the river Maas; landmarks should be

erected in the landscape like the Glowing Man Pole that would be lit from

three sides by a laser beam; vanishing boxes would also be placed in the

landscape and a 'follower of the sunset' that would be about 30 metres

high and from which you would be able to see beyond the horizon. (4)

EARLY YEARS

Gerrit van Bakel was born on 17 October 1943 and was the sixth in a

family of eight children. His father died in an accident while he was

dismantling a gun turret that was left behind on his land after the war. At

the age of eight he went to live with an aunt and uncle in Deurne. His

uncle would prove to have a great influence on his work and ideas, in

particular because of his philosophical cast of mind, his anarchistic ideas

and his headstrong personality.

At the beginning of the sixties he first came into contact with art. He

became acquainted with artists such as Johan Lennarts and Willi Martinali,

whose independent and original life style made a deep impression

on him. "When I made the acquaintance of an artist, I was fascinated, not

by what he made, but by the freedom he had. He had chosen his own way

of life and to my astonishment it also seemed to work. In my view this way

of life was also akin to what happens on the farm. Everything there

functions in the service of a complete process of development with a

beginning, a middle and an end. All the other professions seemed incomplete

to me; they never made a complete product, only a detail of one

or sometimes only a detail of a detail. After that I went to art school, but it

wasn't a success."

This was in 1963. In the paintings that he made in the art school in

Den Bosch, abstract and figurative (people and animals) elements go

hand in hand. During those years he was preoccupied by the work of Paul

Klee. It is a striking fact that he continued to regard painting as being the

root of all his later work. 'I paint with a power drill, 'he said in an interview

in 1984.5 In this interview he also talked about why he left the art school

and gave up painting. He had the feeling that he was betraying his world

'of the open countryside'. At a certain point I got the idea that I was doing

something that was very odd. All those trends in art that we discussed

had never existed in Deurne. It occurred to me that it was inappropriate

here to be making abstract paintings which were the final point of a very

long journey that had its origins somewhere in Italy. The art of painting

originated in the Renaissance, when the poet was commissioned to sing

the praises of his patron's portrait. I realized that even if I wanted to make

an anti-traditional painting, I was still working in a tradition, a tradition

that had ended up here as if by accident and which had nothing to do with

my own world. (6)

In 1966 Van Bakel moved to Helenaveen, a small village in de Peel. It was

during this period that he began to turn his attention away from illusionistic

painting that in his view was too non-committal and started becoming

concerned with the concrete world of things, the designed object.

Perhaps this was also a way of bridging what he experienced as a distance

between art and life. In this shift in focus and activity his frequent

meetings with the architect Arne van Herk and the designer Jos Jansen

certainly played an important role. He gradually developed a very specific

way of thinking about the objects that human beings have made and

invented during the course of history. Later on, in 1980, he gave this view

of the world a name, calling it 'het voorwerpelijk denken', or objectcentred

thinking. He has often given an elegant and highly original

description of this way of thinking - hence the fact that he is often quoted

in this text-, but in the end it is his works, that are the most effective

embodiment of his ideas, since they are 'points of condensation in a

continuous stream of thought' (1982). The step from producing paintings

to making objects-his furniture and later the machines- was in fact

no break. Looking back over his work he said that 'the process of changing

from producing paintings to making machines in fact occurred very

gradually. It was a very logical development. In fact I still paint. My

working method is that of a painter rather than that of a sculptor. When I

make machines I also work with flat surfaces. (7) His machine phase was

however preceded by a period in which he worked intensively on designing

furniture, toys and objects for walls. |

|

|

|

FURNITURE, TOYS, OBJECTS FOR WALLS (1966-1975)

From 1966 on Gerrit van Bakel became more and more convinced that

the world in which we live, and our own immediate environment needed

to be drafted all over again on the basis of elementary needs and very

simple principles. 'At a certain moment I cycled with a couple of friends

to the South of France and went and lived in a cave. That was where I got

the idea, that I would have to redesign the world.*8 Typical of his designs

were the following priorities: first of all the function of the furniture

(sitting, eating, working, storage, etc), then the clear, visibly functional

construction and finally the use of plywood which is a natural easily-

worked material. This second phase in his work is in fact also called

the 'plywood period'. The plywood parts of each piece of furniture were in

each case joined together with iron corner-pieces. Even the one element

of comfort and the only decorative element-the rounded corners-was

due to the fact that with rounded shapes a much more economical use of

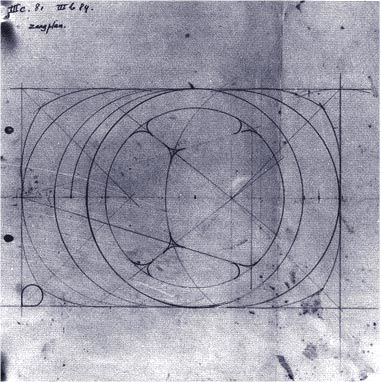

the standard plywood board could be made. The drawings showing how

the wood should be cut for some of his pieces of furniture (for example,

the 'Hymen chair' 1967) show this clearly. Plywood would become Van

Bakel's favourite material, one that he got to know through and through

over the years, in the same way as a farmer knows his own land.

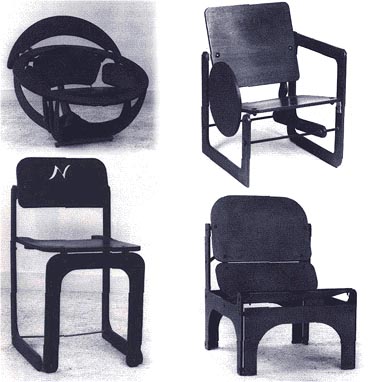

Left: Spinning-chair (1969) |

|

|

|

|

Saw-plan |

|

Top left: Hymen-chair with head-rest (1975)

Top right: Asymetric chair (1971)

Bottom left: N-chair (1966)

Bottom right: Sitting-chair without arm-rest IV (1968)

|

Between 1966 and 1975, then, a very varied series of chairs, kitchen

chairs, stools, sofas, children's chairs, large and small tables, desks,

bookcases and sets of shelves came into being. He also designed tiny

rocking chairs, toys and Wendy houses for children. The basic idea behind

these objects was that a space needed to be provided for the 'original

consciousness'of children. By this he meant "that we shouldn't make

any distinction between toys and any other objects. Coffee pots, mugs or

door mats are just as important for a child as a chair, a doll, a toy car or a ball". (9)

An inventory and description of all his toys and pieces of furniture

can be found in the catalogue entitled 'Gerrit van Bakel, de multiplex

periode', Gemeentemuseum de Wieger, Deurne, 1987. (Multiplex is the

Dutch word for plywood. Translator.).

In addition to their great simplicity and self-evident design, a typical

feature of many of Van Bakel's pieces of furniture is their striking plasticity.

The sculptural character and the attention to form increase sharply

towards the end of his furniture period, as the 1975 series of Hymen

chairs clearly shows. When these chairs are unfolded for the user, they

reveal a variety of complex forms and surfaces. His need for a broader

way of thinking about furniture and for a reassessment of the way that we

relate to our world that is so full of objects, can clearly be seen in his wall

objects. These would turn out to be of great importance for the whole of

Van Bakel's oeuvre. The aim of these wall objects is to make one's home

environment more pleasant by visually compensating for excessive cold

or heat. In a situation where it is too cold they suggest warmth by turning

their red and yellow sides to the front and when it is warm they show their

blue surface so as to provide a visual cooling effect. These wall objects

have to be moved by hand; later on he took them a stage further by

mechanizing the hand movement that produced the complementary

colour effect'. He did this by using the natural phenomenon that par

excellence produces a regular alternation between heat and cold: day

and night. Van Bakel made use here of the typical effect on matter of this

natural phenomenon. It is the first time that the element of movement

appears in his work, a movement that is produced by a mechanism that

harnesses the expansion and contraction of materials produced by alternation

in temperature.

THE DAY AND NIGHT PRINCIPLE

Differences in temperature are most pronounced in the case of the

change from day to night and vice-versa. By day the sun gives the earth

light, heat and energy; at night they disappear and the earth gives back

the heat of the day. The alternation of day and night provides our

existence and the whole of nature with an essential rhythm, which people who

live and work in the country are very conscious of and it is this primary fact

in particular that Van Bakel applied in the 'machines' that he developed

and produced after 1979. He gave the name 'Day and Night Principle'to

this principle of movement which is based on a difference in temperature.

'And then the machines came. They came out of nothing, just like

me. Because I am no more than a medium for forces that exist outside

me. I come out of nothing, out of prehistory. The things that touch me

most closely are prehistoric. My logic belongs to a time before Socrates.

I am trying to catch up with history. In the countryside there are forces at

play that existed prior to history. (10) He applied the Day and Night Principle

not only to small machines that produce a movement that is visible,

but also in the monumental 'Day and Night Machine' of 1975-1977;

this machine that is 8 metres high was first erected outside

the Meyhuis in Helmond during Van Bakel's first one-man show there in

1976 and then on the grounds of the former Technische Hogeschool

(the present Technische Universiteit) in Eindhoven. In the top of this

machine, which is no longer complete, two oval-shaped shields or wings

were attached; the difference between the cold of night and the heat of

day caused an expansion and contraction of two metals, that caused the

wings to lift during the day and to fall at night. In doing this they make a

curve of not more than 90 degrees. The work is almost a gesture of

homage to day and night, an affirmation of the eternal rhythm that all life

is subject to. In this work Van Bakel combines the organic shapes of a

flower or a butterfly with the straight-lined character of a functional

technological construct of steel. Technology here is an accessory that is

used to render visible the powers that operate in nature. On the other

hand this work is a declaration of opposition to current technology, which

in his view had betrayed its own origins.

With this work Van Bakel made his definitive entrance on the terrain of

the visual arts; he was no longer concerned with redefining extremely

concrete objects of everyday use such as items of furniture, but rather

with thinking about and going in quest of the origin of forces in nature, of

phenomena such as movement, time and temperature. The creation of

objects and that of art were moreover very close in his view. Art and

objects are neighbours. 'It is at the point where things are summarized

and reformulated that images, thoughts, forms and possibilities of identification

are generated. This begins with art. This is art history, but we

see that this is a good road to follow. Its climax would be a redesigning of

the world. (11) |

|

THE MACHINES

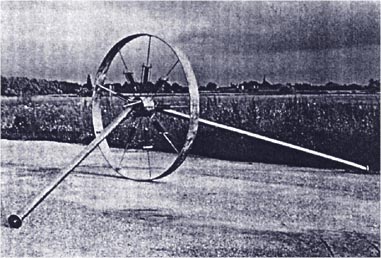

In the next few years, 1976 to 1981, he produced machines in which the

kinetic principle was given a variety of different forms. Movement did not

only occur in a vertical direction as in the 'Rabbit', 1978-1980

which only moves its ears, but also horizontally, for example

in the two 'Circle machines', 1979-80, which are day

and night machines on wheels. As a result of the influence of the alternation

between heat and cold these machines draw a circle in pencil or

chalk over a period of three months. In this way the principle of day and

night is rendered visible but extremely slowly.

In this machine and in other ones wheels make their appearance.

They are an element that in terms both of function and of form play a

considerable role in the work of Van Bakel. The fact of going forward, of

moving from one place to another, fascinated him. Once again in order to

make their origin visible he gradually looked for and eventually discovered

a new form of power and the technology needed to execute it. The

alternation in temperature between day and night and the difference in

the coefficient of expansion of different materials were the natural element

he required to design machines that move extremely slowly. He

therefore accepted being dependent on forces over which he had no

influence whatsoever. This was certainly the case with his splendidly

constructed 'London machine', in which he used mist as a

source of energy instead of heat and cold: the expansion and contraction

of nylon threads. The counterpart of the 'London machine' is the 'Berlin

machine', 1978-1980. This machine only moves at night in

response to the expansion of brass wire.

All these machines for 'driving'-he even called one of them 'Little

Automobile' are not simply an ironic comment on our advanced

technology, but are rather a fundamental criticism of it and

certainly when it is applied to the design and production of cars.

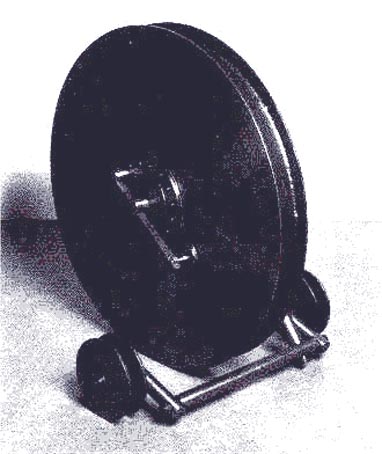

Right: Utah machine (1980) |

|

|

|

The most succinct example of this is the 'Utah Machine', 1980,

that 'takes on' the 'Blue Flame' rocket, that achieved the world land speed

record in the Utah salt flats. This rocket reached a speed of 750 mph.,

faster than sound in other words; the 'Utah Machine' covered 18 mm per

day. The latter machine was 'driven by the sun' and in fact is nothing

more than a moving wheel held up by a pair of supporting struts. The

shape of the wheel is a metaphor for movement. The counterpart of the

'Utah Machine' is the much bigger 'Tarim Machine' which

was intended to cross the Tarim basin in Tibet on the other side of the

world, a distance of 1100 kms. The concept for both machines originated

during the years 1979-1980. He gave them the combined title, 'The

Utah-Tarim connection'. Theoretically the Blue Flame would be able to

cross the Tarim Basin in an hour, while according to Van Bakel's calculations

the 'Tarim machine' would take 30 million years to cross it. 'The

connection is complete when: a. the machines are constructed, b. the

press reports have been distributed across the world, c. the journey of the

'Tarim machine' is completed. During the course of its existence the

'Tarim machine' can be altered or replaced.

The 'Tarim machine' that was constructed later on in 1982 for the

Documenta 7 in Kassel is much larger and more complicated than the

'Utah machine'. This machine that is six metres in length makes one

think of a caterpillar-like animal that with its four antennae and numerous

feet can continue for ever on its way across the desert without any

interruption.

It is clear from both machines that Van Bakel does not resort to

reflection or to language but realizes and makes his ideas concrete

through the machine itself. In this case these are ideas about the meaning

of speed and time rather than about movement. 'It advances on its

little feet one little step forward in the desert. Over sand, salt, rocks, and

up the sides of mountains. Even if it falls over it makes no difference. The

fact that it has to take so long to go across the desert is itself a part of

what it is all about: time and not movement. (12) Van Bakel makes the

notion of time a relative one and reduces it to proportions that a human

being can understand. 'Just imagine that the Tarim basin remains un-

changed and that the grandfather in his hut is saying to his son, 'you see

that machine that is moving towards us. You will have to tell your grandson

that when he builds his hut, he will have to build it a little bit to the

left; otherwise the machine will ride over it. (13) This conceptual moment is

the heart of the work, but the form in which he has given shape to his idea

is also of the utmost importance for Van Bakel. In an interview in 1980

with the physicist Dr. Hans Beltman that is crucial to understanding his

work and ideas, Van Bakel talked about the relation between ideas and

form. "Art is about things, about forms and a form has to include a

message about the road that has been taken to arrive at that form. It has

to be contained in the form. If you only show the finished goal, you are no

longer involved in anything more than some reduction or other. If you only

show the process you are involved in something that is merely theatrical. I

want to do both things at once. I want to show not just the form but also

the road I have taken to arrive at it and this means that my sketchbooks

are just as important as the machines and the other things and that

everything overlaps with everything else. I want to show people all this all

at once. Of course you can't do that. So people have to take their time

about it and get to know what I am doing bit by bit and become enthusiastic

or share my own enthusiasm with the things that I have made. My

attitude, my attempt to achieve a harmony with the subject, if this is

correct or convincing, if it possesses the right degree of power then it is

there also for other people. Of course it is not the most effective way of

sharing one's feelings, but perhaps it is effective in showing how I think

about things. However-and this is a disadvantage in my work-my explanation

of it is indispensible. As far as that goes I am not a real artist. At

least not in the classical sense, the notion of the artist who only gives you

his image, who gives material form to his emotions. I start with the

assumption that the people who see it also have thoughts. If they also

have thoughts then in fact I don't need to say anything. Then they will

figure it out for themselves. And they can hardly go wrong there, because

what I do is not unambiguous. I am not just dealing with something like

heat = movement. It is just that I have paid a lot of attention to heat and

movement because that is something that is difficult. I don't really want

to specialize." (14) |

|

|

|

THE SUMMER WHEEL 1982-83

A third important work that has the Utah-Tarim theme is the 'Summer

Wheel', 1982-83, which however was produced much later on.

In this work Gerrit van Bakel has once again presented us with a

discussion on a very large scale, this time of the wheel, one of the most

important human inventions. It is striking that he has paid plenty of

attention to formal plastic features; the wide tread and the long rods that

keep the wheel steady and contain the oil tanks give this machine a

monumental force.

During the years 1979 and 1980 a striking expansion of the contents of

his work occurred: he put a number of important inventions and discoveries

in the field of technology and culture in a historical perspective,

often by bringing them together in a single work. Sometimes he draws a

direct connection between technology and nature by referring with some

emphasis to the origin of the invention, as for instance in 'Small concert

for laser, bulldog (tractor) and bird', 1979, that he produced

a number of times.

Left: The Summer Wheel, 1982-1983 |

|

In comparable works from a later period he tried in the first place to evoke and again bring back to life the crucial moment of creation and, above all, before the creation of important works of the past in the fields of art, nature and technology. This is also at

the core of the work 'Back to the source of the search for the origin of

Albinoni's grief', 1980 that was the subject of a performance

at the opening of the first major exhibition of his work in 1981 in the

Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. For this performance that was directed

by Van Bakel himself in the guise of a scientific researcher and magician,

he conducted an experiment, consisting of an iron bottle containing gas,

a burner, steam, mirrors, a blue lamp, a helium neon laser, and sound

equipment. With the aid of a steam turbine engine he got the laser beam

to trace a red circle, which rose slowly due to the increasing pressure of

the steam. Together with the hissing of the steam one could hear the

stately sounds of the 'Adagio' of the baroque composer, Tommaso Albinoni

(1671-1750). All these different elements contributed to the magic of

the moment when the circle reached its highest point. With this extraordinary

moment where technological achievements and discoveries

through the ages-such as glass, iron, the steam pumps of the Greek

physicist, Hero of Alexandria (1st century BC), perspex, the reproduction

of sound, laser beams, and the sorrowfulness of Albinoni's music were

brought together, Van Bakel wanted to refer to the creative moment

itself. Many of Van Bakel's works are a sort of homage to this 'sacred

moment' while at the same time being an attempt to 'recapture this

fundamental silence'. (15) In Dr. Hans Beltman's interview with him in

1980 Van Bakel said about this: "My idea here is the sort of awareness

that exists before something has been created. Something that has not

yet been thought of. The relation that exists between Hero's attitude as a

man involved in research and Albinoni's attitude and my own attitude,

which moreover is also an interpretation of that of Albinoni and Hero, this

attitude of mine is to bring these people together. I have such a mournful

feeling if I think of the night before Albinoni wrote his adagio. I can

imagine him so easily, and Hero too with his little bail of steam... I think

that something happened then. People like this make themselves open

so that they can arrive at a discovery, it has something to do with being

vulnerable. Maybe I am sentimental by nature." (16)

Personal elements occupied an increasingly important place in his work

as we can see from the 'Eindhoven presence machine' that

was made for the same exhibition in the Van Abbemuseum. In this object

damp soil from Van Bakel's birthplace was heated; the moisture rising

from the soil causes the ropes that are joined with two wooden rings to

contract. As a result these rings shift slowly in relation to each other. This

was not so much a question of the soil itself - what does 'native soil' mean

anyway? - but of the concrete reference to the region that he came from:

de Peel. He also planned the 'Glowing Man' to be constructed in this

region. He had designed two huge horns for this project that

would function as voice amplifiers. These horns would be erected in the

fields at a great distance from each other. Through them his brothers and

sisters could tell each other things about the landscape, the landscape of

their youth, without raising their voices. An aid to communication about

nature between people. |

|

RESEARCH AND POETRY

In 1981 striking changes appear in his work and concepts. The abovementioned

major exhibition in the Van Abbemuseum and his moving to a

new house with a large studio -an old factory premises -on the outskirts

of Deurne certainly played a part in this. His work became rapidly better

known particularly after he was invited by Rudi Fuchs to take part in the

Documenta 7 in Kassel. Even before 1981 he shows signs of a utopian

and more magical way of thinking about the world and about the objects

that human beings have surrounded themselves with, as Dees Linders

points out in her article. A typical feature of his work is his need to look for

the origin of things and to try and find a harmony with nature, a harmony

that the technology of the 20th century has lost. The word 'harmony'

crops up with increasing regularity in his sketchbooks. 'Harmony is the

prototype on which my story is based. (17) His notions about the function

of his work are idealistic and of an almost romantic utopianism. Van Bakel is

convinced that the object in its development from neolithic times to the

present has lost its way. 'Redesigns will have to be made. All over again,

beginning at the beginning with an attitude that was already present in

the distant past. The linking up of poetry with science and with tech-

nology in particular. (18)

He hoped that he himself could play a role in this

reformulation of the world of objects by designing his objects and his

machines that he deliberately described as art. 'Let me try and find a

place for myself in the art of the past 50 years. I cannot see further back

than that. I hope that the things that I make, or at any rate a number of

them, will form part of the idiom, the idiom of the objects that people will

require 10, 100 or 1000 years later in order to arrive at a definition of the

world of objects. In this sense what I do can be compared with fundamental

scientific research; even though I am myself not a researcher. I do

not define myself by saying what I am doing but by doing things and

letting people see what I have done. The result of my activities is a thing,

an object and not a word. (19)

Right: The Seismograph - the Nights of Richter (1982) |

|

|

|

After 1981 a more realistic investigative attitude also began to appear

in Gerrit van Bakel's work alongside this idealistic and utopian

attitude; this was stimulated above all by his astonishment at natural

phenomena -on the earth and outside it- and by discoveries in the field

of the natural sciences, which he once described as a 'cool phenomenon,

that also represents emotion!' He looked for a closer connection with

these sciences: mathematics, physics, chemistry and research into outer

space. He read a great deal of literature on the subjects of technology

and physics and he made contact with physicists at the University of

Technology in Eindhoven.

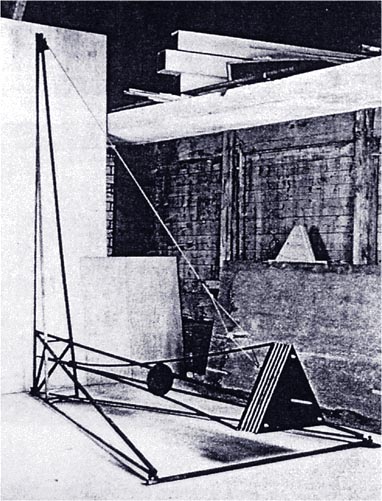

He continued to be inspired by the moments in which the great scientists of history came up with discoveries or inventions that turned out to be very influential. These moments of inspiration, prior to the experiment or the realization of an idea, formed the point of departure for works like the 'Papin machine', 1981 and 'The Seismograph (the nights of Richter)', 1982. In the

former work there are other elements that also play a part. The occasion

for the 'Papin machine'-one of the most powerful and influential of all his

works -was the invitation from Rudi Fuchs, who at the time was director

of both the Van Abbemuseum and of Documenta 7 (1982) in Kassel, to

contribute to the Documenta. This was of course both a challenge for him

and an acknowledgement of his quality. In Kassel Gerrit van Bakel exhibited

four works, including the 'Tarim machine', 'The shape of a terror

(atom bomb)', 1980-1982 and the 'Papin machine'.

It was the stratified character of his work in particular, the

bringing together of very different elements that are typical of the way

that Van Bakel often constructs his work only gradually to expand on it

later. The subjects come from the history of science, from recent world

history and from his own personal history. They are also a product of his

idea about the relation between culture and nature, between raw materials

and technology, and about the physical element in the metaphysical.

He literally found the concrete occasion for this work in Kassel which he

visited in 1981. In a square there he saw a memorial tablet commemorating

the fact that the French physicist Denis Papin (164 7-1712) had

tested out his invention of the steam cylinder there in 1695. The full title

of this work, 'A new possibility of Papin's joy' refers to the joy

of the moment when the idea came to Papin to develop through the

compression of steam a force that would be countless times more powerful

than that of a human being. Afterwards, by means of numerous

sketches, an associative process began that led to a machine that would

be capable of raising a heavy slab of granite with a pile of sand on

it. The four supports with the steam cylinder and piston in the middle comprise a

sort of sacrificial altar, an open structure of iron tubes and bars, narrow

below and broad on top. So far all it is is an entirely new design for a steam

engine, a sort of reexperiencing of Papin's discovery. A second essential

theme in this work is however the death of Gerrit van Bakel's father, who

died just after the Second World War as he was dismantling a gun turret.

He was hit by a spring that shot out of a tube under a high pressure of oil.

The soil on the granite slab came from the field where his father had died.

This became the symbol of his father's death and at the same time a

reference to his native soil. It is probable that Van Bakel chose granite as

the material for this 'altar' both because it is a very solid and long-lasting

material and because of the classical significance of this stone for sculpture

and the fact that it was used for altars in Catholic churches.

The 'Papin machine' does not produce anything; its only purpose is to

raise the heap of sand a few centimetres and in this way to pay homage to

his father and perhaps in a more general sense to the earth, to the source

of all life. The idea of a sacrifice of earth is not only suggested by the

towering form of the construction-small below and wide above-and by

the granite slab, that gives one the picture of an altar, but above all

because of the literal lifting up of the slab and the sand.

The form and function of this machine give enough reason to believe

that its creator has tried to give one the idea that he has made a

connection between the material (sand and granite) on the one hand and the

immaterial, the indescribable or 'higher' on the other hand. Human

beings (particularly as a group) have an enormous need for a certain

amount of 'mystery' (sketchbook, June 1979). Thinking in terms of a

unity between the two areas was nothing new for him. He was very open

to making connections of this kind, as one can see from the comments

that he made on his own works. In the case of the 'Papin machine' he

would seem to be referring to a connection between technology and

nature, between the physical and the metaphysical, between life and

death, but also to the connection over the centuries between the physicist

Papin, the farmer (his father) and the artist that he was himself. (20)

The 'Papin machine' was made at the beginning of the third and last

period of his work. In this period that begins with the year of his first

major retrospective exhibition in 1981 and ended abruptly with his death

in 1984, changes appear as I said earlier in his way of thinking and

working. He becomes increasingly concerned with questions about the

character of natural and physical phenomena, and how we perceive and

record them, and less with the magic of unaccountable forces on this

earth and in the universe. With one group of works at least this is the case:

with the 'Tetrahedron', 1982, the 'Seismograph', 1982, 'Concerning

cold', 1983, the 'Telescope for the Pole Star', 1983, the 'Perseids tele-

scope', 1983, the 'Experimental construction Oil l and 2', 1984 and the

'Gyroscope', 1984. |

|

|

|

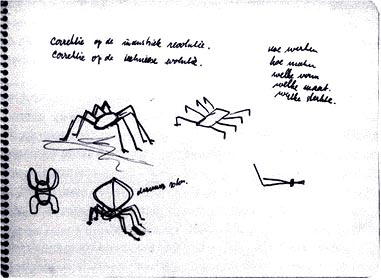

Top: Drawing for Spider' (never realized)

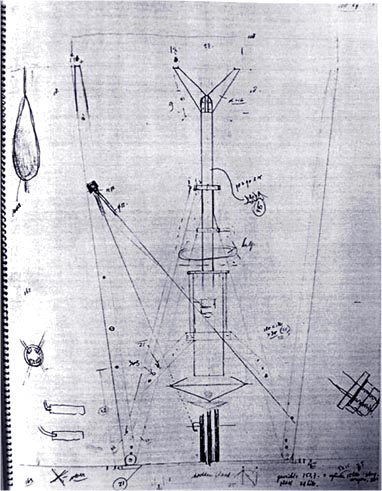

Right: Drawing for Papin.machine (cat. nr. 40)

The function of measurement is of course the most important aspect of

the 'Seismograph'. This work results from his astonishment

at the phenomenon of the earth, that is constantly in motion: 'the earth as

a round object, a system like a sort of slowly vibrating pudding. (21) And

this led to a question about a method for recording it, without making use

of existing seismographic instruments. 'Daydreaming with a piece of

paper. That's something that I always do. I try and imagine something

and I let my hand lead me. Every day. In the course of time a certain

sketch recurs with increasing frequency in my sketchbook. During the

past few months I have maybe drawn the seismograph a hundred times in

my sketchbooks. It begins to become serious if the moment is right and I

pick up a ruler. It acquires a measurement, a form and a comment on its

feasibility. |

When I was finished with the seismograph I was quite pleased.

I had a shower, put everything straight again in the kitchen and went to

bed. But I couldn't fall asleep. I imagined the movement of the earth. A

seismograph is a thing to measure earthquakes. The earth is a system of

waves and vibrations. This stable thing on which I live is always moving.

Very slightly. Very slowly. However still I am sitting, I am never quite

still. (22) And elsewhere he adds: 'The earth moves with intervals of 8

seconds. What I experience then is the fact that I am standing on a

moving earth, and this is the feeling that I want or hope that someone

who sees that thing and thinks about it, that he will also get that feeling a

bit. (23) Van Bakel wanted this instrument not just to make vibrations

visible and palpable; he also wanted to refer to the history of the seismograph

and to pay homage to the man who by establishing these

measurements had devised the system of scales of magnitude for earthquakes,

the American seismologist Charles Francis Richter (born 1900).

'Six and a half on the Richter scale. That was something that used to be

mentioned in news items. A sound. For me Richter has once again

become someone who pottered around in a shed with a lot of suspended

weights. The name of Richter will certainly be remembered for a thousand years.

But nobody still remembers that Richter was someone who

ate sandwiches. I now know that he did. Did Richter have a father? Why

did he begin to work with these vibrations? That's the sort of question I

ask. I don't have to know the answer; all I need is the space to conjecture

how it took place. This is the feeling I'm looking for. I share a fraction of

his consciousness. This feeling must continue to linger in the form of the

seismograph. What I make, it's an ode to the nights of the people who

have lain tossing around in their beds. And have invented something. It is

the frontiers of consciousness that interest me. A consciousness like this

can take on very dramatic forms. People who live in a state of tension,

often have dreams about earthquakes. In actual fact a seismograph is the

opposite of an earthquake. The invention of the seismograph has something

to do with the overcoming of fear, the exorcizing of fear. This is in

fact true of most technological inventions. They are aids that help us to know where we are. And what is going to happen. Consequently the

essence of the form gets lost in the course of time. (24) It is the same sort of

ode as he made to Hero of Alexandria, to Albinoni and to Papin. Moreover

he also saw the absurd aspect of his undertaking, of inventing something

that already exists: 'What I'm concerned with is of course total nonsense.

Who would do a thing like this nowadays, making a seismograph in

Deurne? (25) But at the end of John Heymans's interview with him that

took place just after he had made the seismograph, he described with

great accuracy what in fact led him to making all his objects. I am

looking for the form of the technology which is rarely the same as its

subject. I don't invent any seismograph. What I do is to individualize a

notion such as that of a seismograph. This is a very emotional process. I

do all over again, as it were, everything that has ever happened. In a

different way. The objects that I make are in fact no machines. I only call

them that. What is a machine, in actual fact? Is the wheel of fortune a

machine? Is a try-your-strength machine really a machine? No matter

how odd they may look, most machines make products. My machines

don't make any products. They produce consciousness. In this sense

however my machines are machines after all. (26)

Another, quite different, measuring instrument is the 'Telescope for the

Pole Star', 1983. In this case the subject of the research is

not the earth but the universe: his dream was that he would be able to use

it during daytime to see the most important point of reference through-

out the ages, the Pole Star. This could be done by eliminating the influence

of the earth's diffused light by means of two long tubes (6 metres)

through which one would look at the star. The viewer gazes through a

dark tunnel and at its end he sees a point of light: one can imagine that

one is looking directly into the universe. This large telescope, that combines

with a globelike structure halfway along to form an open construction,

connects the place where he (and the earth) are situated with the

infinity of outer space. It is this awareness that this machine aims to

stimulate in the person that uses it.

Van Bakel also continued to search for new forms for producing

movement as for instance the 'Winter Trolley', 1982-84 that works by the expansion of ice and which has a splendid vertical form due to the column of ice required for the piece. The column itself is crowned

with an adjustable flower calyx for catching the rainwater. This 'Winter

Trolley' is an immediate precursor of the 'Rain Trolley', 1982-83.

When the receptacle of this trolley is filled with rain water, it

tips backwards as a result of the shifting of the centre of gravity and the

rain trolley makes a big lurch forward, which causes the sticks to go up.

'It prays for itself and it applauds itself. (27) Here too the form is determined

by the function, but as a result it also acquires a primitive archaic

character. A special feature are the wheels that were executed following

a very original design and principle. 'These wheels, they are wheels that

are made of a flat plate, that I have sawed out and bent so that I have

turned something that really isn't at all strong into something that will

take the pressure of 80 kilograms per wheel.'

During his last period Van Bakel did not only make works whose

purpose is measurement and movement; he also made a number of

machines whose meaning is much more complicated and that bring

together many different elements-historical, cultural, personal and

sometimes philosophical. What they have in common is that they do not

have any practical function, but are vehicles for an idea or belief of their

maker. In this sense these works are pure art, they only refer incidentally

to technology or physics. Form also begins to play an increasingly important

role and occasionally there is a work that is only made for the sake of

the image, such as the 'Medium-sized carrier of problems', 1984,

where the important thing is the plasticity of the huge

adjustable wheels and the tension of the bow. The only function that this

thing has is to be there.' The egg trolley which he named 'Concerning the

origins of piety', 1982 cannot move, but it does however

have an adjustable mechanism and massive metal wheels. It is the product

of Van Bakel's great love for metal in all its forms and his admiration

for all the smiths who have worked these metals with great love and

knowledge. By hanging two eggs from the upper part of this trolley, he

adds another dimension to this work of homage to the smiths of all times.

He brings the iron into relation with an object of nature of great

perfection. 'They belong together in my opinion. An egg and an iron bar are

equivalent objects. The moment that you pick up these objects you are

involved with what men call the Divine. In my view therefore it is a sort of

summing up of religion. Piety is the fruit of human beings' ability to

make abstractions, and to take a distance from things. (28) This work is

typical of his associative way of thinking and working; his commentary

shows how the material- in this case iron -and the processing of it in the

service of technology was what preoccupied him. The most fascinating

thing about this trolley is the marvellously poetic combination of the eggs

and the iron construction. Here perhaps he succeeds in rendering visible

and tangible something of his never explicitly stated notion or assumption

that there is a unifying principle at the basis of the whole of matter

and of nature and human life. |

|

|

|

The other trolleys that he produced in 1984 or just before are also a

representation of an idea or story in the form of a vehicle; as for instance

the elegant 'Baldur trolley', 1984, that the young German

god Baldur is said to have made with his uncle to ride to follow after

Donar, the god of thunder and to make wind. Or the two 'Trolleys for

good and evil', 1983-84, whose structure and symmetry

stand for dualistic thinking, including the many limitations inherent in

this way of thinking. The trolleys become messengers bringing a poetic

or philosophical content. In making the wings of the 'Baldur trolley', for

instance, three metals are used; iron, copper and aluminium, because

Baldur was no longer able to tell his uncle that it was absolutely necessary

for these to be used. For this reason Baldur's chariot was incomplete. Van

Bakel added these metals with their magical power for humans to the

trolley. 'I have now added these three elements to this fan-like structure. I

thought that there should have been a spell, that an exorcism should have occurred and that because this exorcism did not happen, Christianity

arose with one God in three Persons. Because these three things were

left out and because the Trinity began to play a role, it took much longer

before men were able to fly. That they failed to follow in the steps of

Icarus. (29)

The seven 'World trolleys', 1984 brought a small quantity

of Van Bakel's native soil to very different places over the whole world.

Two of them have already completed their journey and are concealed in

the temple in Incallatja in Bolivia and in the Acropolis. The native soil is a

metaphor for his own person and for the significance that he attributes to

the earth in general. The trolleys too stand for what is an essential value

for Van Bakel, that of metal; they are made of five different metals: iron,

copper, bronze, brass and aluminium. The great precision with which the

trolleys were designed and produced attest to the great advances in

technological knowledge that have taken place during the second half of

the 20th century. For those who will maybe come across them in centuries

to come, they comprise a link in the chain of the development of

technology, but here too they refer back to their origins, the earth, that is,

that the trolley contains.

In the last year of his life Van Bakel worked very intensively on a number

of major projects. One of these was 'The Wheel', 1982-89

that he was commissioned by the Energiebedrijf Tilburg NV (gas and

electricity company) to make for an outdoor situation. The company

devoted a very informative publication to this work. The theme was

stated in Van Bakel's own words, 'At the end of the age of the machine it

would seem to be a good idea to offer a large-scale and simple homage to

the Wheel. (30) 'The Wheel' was indeed one of his largest machines; it is

6.30 metres high and has a rotational radius of 8.10 metres. On one side

it is supported by a shaft, that is fastened at one end and in which oil is

placed. It moves in an extremely slow circle on its broad rim and it is

propelled by the heat of the sun: 'a sort of ETERNAL energy'. A filter and

a transmission device causes the oil to expand so that the wheel is

pressed a tiny bit forward. Its site in particular makes ita comment on all

the known and accepted forms of energy. In fact the wheel has constantly

played a part in Gerrit van Bakel's thought and work.

Left: Concerning the Origin of Piety (1982) |

|

It has always intrigued him because of its powerful form and its numerous symbolic implications but also because it is one of the few things that do not have any obvious prototype in nature. He talked about this during a lecture at

the Art Academy in Kampen, in March 1984, just after he had completed

the drafting stage for this work. "When the wheel first appeared, there

was no natural reference point for that wheel, a rolling stone perhaps, or a

rolling tree trunk, but, that's all very well, but it still isn't a wheel, a wheel

is something a little bit more subtle, because it contains the possibility of

being able to leave the world behind some day and that is what is in fact

happening now, people are working with the help of rockets to leave the

system and framework of the earth behind (...). That wheel is thousands

and thousands of years old, it has taken thousands and thousands of

years for it to reach a certain degree of sophistication (...) so that while

you no longer see anything of a wheel, because a rocket doesn't look

anything like a wheel, people can leave the place where they are behind,

this is something so gigantic, it is almost inconceivable." Van Bakel died

just after he had made the detailed draft for 'The Wheel'. Fortunately

during the next few years, 1984-1989 the project was realized as a result

of the combined efforts of many people.

The second large-scale project was an enormous sowing machine,

that once in seven years would pour out seed over the fields. The machine

would be activated by rain that would be collected in a system of containers.

The commission to produce this work came from the Academisch

Medisch Centrum, a hospital and medical research centre in Amsterdam.

The draft drawings that he made for this project are splendid, but

because of his premature death in the night of 18 to 19 November 1984,

the project was never realized. In the Summer of that year another

exhibition of his work was held entitled 'Uit de Werkplaats' (from the

workshop), that covered all his work since 1981. The catalogue that

accompanied that exhibition contained an exceptionally interesting in-

terview with Gerrit van Bakel by the curator of the museum, Piet de

Jonge, in which he talked about the background for a number of his

works.

In the months before his death he produced more theoretical and philosophical

statements than he had done so far about the world of objects.

He wrote columns in the magazine, 'Delta'. In September 1984 he gave a

lecture entitled 'Elements from an artificial landscape'. This was held in

the context of the 'open day for philosophy' at the Technische Hogeschool

Twente in Enschede (a College of Technology).During the reading the speaker's

chair rose slowly so that at the end of his lecture Gerrit van Bakel could

look out of a high window. At that moment he was discussing the horizon

and the phenomenon of sunset.

FROM THE PEEL TO THE UNIVERSE

The sunset was also the theme of one of his last works, one that was never

finished, the 'Follower of the sunset'. For 'Follower of the Sunset III',

1984 he made a construction of two very long poles, at right

angles to each other; anyone who wanted to follow the sunset and to

extend that moment could use this device which rose very slowly. The

work is about the elusive quality of that impressive moment that to the

primitive mind was a moment of terror. 'What the horizon suggests tome

is the idea that we as followers of this primitive way of thinking, as

creatures with the faculty of looking, once upon a time came to realize

that that same sun also rises. ' 'This Follower of the sunset 'should also

have been situated on the piece of land in de Peel where all the lines in

Van Bakel's work come together: in the unfinished project 'Glowing Man'.

The concept of the 'Follower of the sunset' is particularly poetic and

magical. It renders visible something of his efforts to step outside the

limits of the earth and to continue with his research in the universe. In

fact he had already on a number of occasions stated in his notebook his

desire to free himself from the earth and to fathom the immensity of the

universe. Words such as 'levitation' and 'floating' occur regularly. As

early as June 1979 he wrote in his sketchbook, 'whether or not a work of

art is (or is capable of being) Marxist is not relevant because the adventure

involved in understanding and in floating is much more interesting

than any involvement in social events that may take place in a radius of

a. 10 b.100 c.1000 d.1O.000 kms around us'. This desire is also the

basic theme underlying a number of his works, such as 'The telescope

for the Pole Star', the 'Perseids telescope' and the 'Seismograph'. 'My

reason for making that thing was in fact the desire to leave the world

behind. (32) His deepest ambition however went beyond research and measuring.

What he wanted above all was to arrive by means of his objectcentred

thinking at the common origin of science, technology and art,

because there was a unity there of intellect, emotions, intuition and

respect for the earth and for nature. He dreamed above all of 'a sort of

redesigning of the world' (1981). His dreams were quite without limits.

In a note in one of his last sketchbooks one can read: "Of course I

want to redesign the universe, but that is something that I cannot do."

Jaap Bremer

In writing this essay I owe a debt of gratitude

to a so far unpublished doctoral thesis, 'Gerrit van Bakel 1943-1984, van de Peel naar de Peel met een omweg langs de wereld' by Dees C.M. Linders (Groningen 1989). (Gerrit van Bakel 1943-1984, from de Peel to de Peel with a detour by way of the world. Translator). This in-depth analysis is indispensible for anyone who wants to understand Van Bakel's oeuvre.

Notes:

1. Interview on the Brabant local radio station, 13.6.1982.

2. 'Naar de harmonie van het karrespoor', a conversation between Gerrit van Bakel, Dick Paaymakers and Victor Wentinck, Delta, 20.12.1983.

3. Exhibition catalogue, 'Gerrit van Bakel, Het voorwerpelijke denken', p.28, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven.

4. D.Linders and others, 'Gerrit van Bakel, Het Wiel', p.9, Energiebedrijf Tilburg NV, 3.1.1989.

5. Anna Tilroe, 'Gerrit van Bakel, Ik schilder met de boormachine', Haagse Post, 25.8.1984.

6. Idem, p.42.

7. Gasuniek, 20th year, no.25, December 1984, p.30, Gerrit van Bakel.

8. R. Boonstra, 'Machines om je wang zacht te maken, Gerrit van Bakel op de Dokumenta', Elsevier Magazine, 19.6.1 984.

9. Exhibition catalogue, 'Gerrit van Bakel, De multiplex periode', p.8, Deurne, 1987.

10. R. Boonstra, idem.

11. Exhibition catalogue, 'Gerrit van Bakel, Het voorwerpelijke denken', p.16, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 1981, interview with Dr. Hans Beltman.

12. TV interview, Teleac, 1982.

13. Exhibition catalogue, 'Gerrit van Bakel, Het voorwerpelijke denken', p.30, 1981.

14. Idem, p.35.

15. Sketchbook, June 1979.

16. Exhibition catalogue, 'Gerrit van Bakel, Het voorwerpelijke denken', p.11, 1981.

17. Idem, p.15.

18. Idem, p.24.

19. Idem, p.21.

20. In the above-mentioned unpublished study, 'Gerrit van Bakel 1943-1984, Van de Peel naar de Peel met een omweg langs de wereld' (1989) by D.C.M.Linders this work is discussed and analyzed in depth.

21. 'Gerrit van Rakel, Uit de werkplaats', p.11, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 1984.

22. John Heymans, 'Een ode aan de nachten van Richter', an interview with Gerrit van Bakel on 7.11.1982, p.18.

23. 'Gerrit van Bakel, Uit de werkplaats', Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 1984, p.11

24. 'Een ode aan de nachten van Richter', p.20.

25. Idem, p.19.

26. Idem, p.20.

27. 'Gerrit van Bakel, Uit de werkplaats', p.31.

28. Idem, p.55.

29. Idem, p.59.

30. 'Gerrit van Bakel, Het Wiel', Energiebedrijf Tilburg, 1989, with articles by Dees Linders, Nico de Glas and Guido Lippens.

31. See Gerrit van Bakel's lecture 'Elements of an artificial landscape'.

32. John Heymans, 'Een ode aan de nachten van Richter', p.19.

|

|